Who Has a Better Pricing Strategy: Netflix or Amazon Prime?

“Nicholas” … “Niiiicholas, can you come here a minute?”

Every Sunday I try to make it home for family dinner.

Without fail, a question about technology is raised — typically by my mom, since my dad’s a Luddite (still using a flip phone, you go dad!).

Last night was no different. Half an hour after dinner was finished my mom had her laptop open and a question on the tip of her tongue.

“Netflix has changed their prices,” my mom says. “Come take a look at this email.”

This has been a long time coming. When Netflix raised its original price from $7.99/month to $9.99/month back in October 2015, experts knew the lower price point wouldn’t last.

If you were one of the early adopters, like my family was, you were grandfathered in at the $7.99 price point.

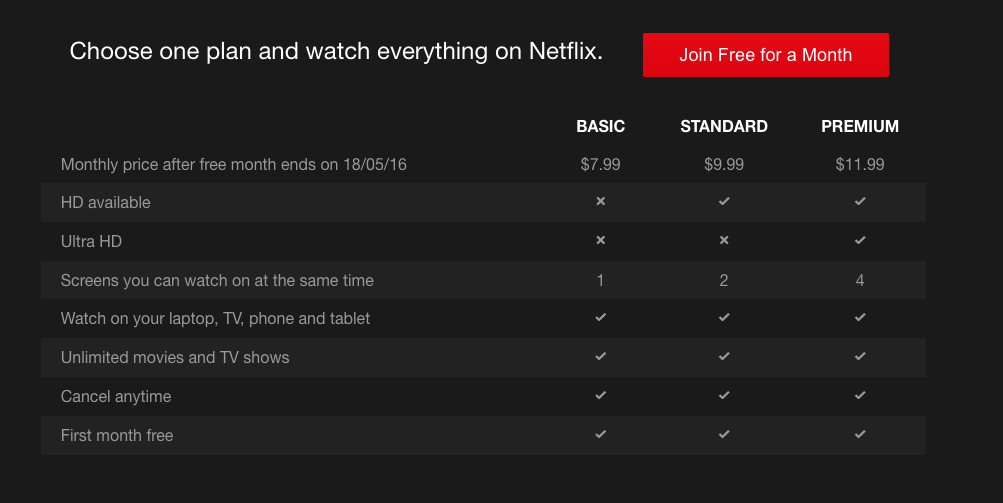

Now, Netflix is offering three new pricing plans: Basic – $7.99/month, Standard – $9.99/month, and Premium – $11.99/month.

All subscribers who were grandfathered in at the $7.99 price will be automatically upgraded to the $9.99 plan unless they choose to downgrade.

The question then becomes, do you pay $2 or $4 more for the same or slightly better service; do you keep the same monthly price and downgrade your service (Netflix’s basic package doesn’t offer High-Definition streaming); or do you cancel altogether?

This change in pricing has a lot of investors nervous. Last week, Forbes wrote about the changes and how they might affect Netflix’s stock price.

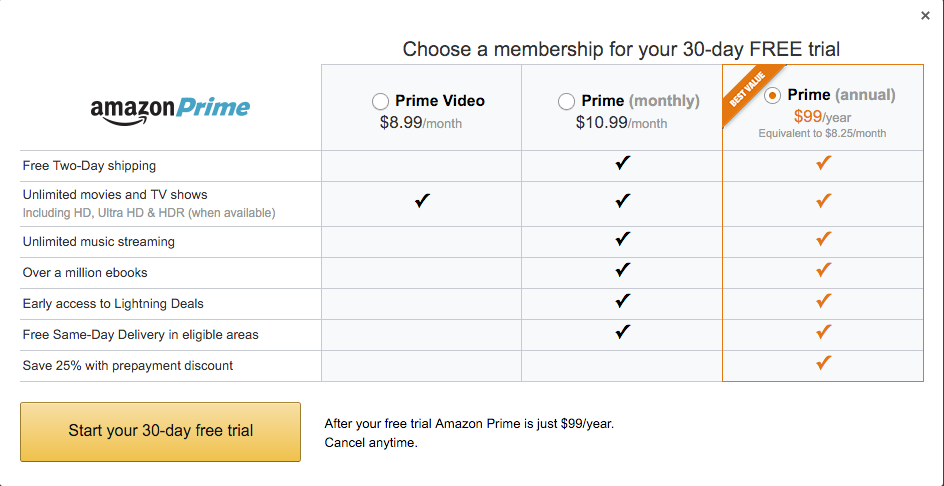

Also, it’s no coincidence that Amazon has now announced it will start offering new pricing options for Prime memberships. Likely to entice unhappy Netflix subscribers who are considering jumping ship.

Instead of just having the yearly $99 Prime membership, Amazon Prime members can choose between a monthly option of $8.99/month (Prime-video only); or $10.99/month (full-Prime service); or stick with the $99/year membership.

Today, I’m going to explain why Netflix and Amazon do their pricing this way and show you some cool pricing strategies you can use to sell your own subscription services.

Here’s a look at the new prices for both Netflix and Amazon Prime:

The first thing you’ll notice is both companies use what is called Charm Pricing — prices that end in 9, 99, 95.

Studies show that conversions are significantly higher when companies use Charm Pricing. The mistake most businesses make, however, is they credit the higher conversion to the 9s. That’s not the case. There’s another factor at play: the left digit.

By reducing the left digit by one you see higher conversions. A one-cent difference between $7.80 and $7.79 won’t matter. However, a one-cent difference between $8.00 and $7.99 will make all the difference.

Another strategy you might have heard being used in pricing is the use of rounded numbers when selling is considered to be emotional. Studies show that when a purchase is rational, unrounded numbers convert higher. That’s why home buyers pay more money when prices are specific (e.g., $362,978 vs. $350,000).

But when a purchase is emotional, like say a TV subscription (Don’t miss out on the latest TV shows, sign up today!), round numbers convert higher because they’re processed by the brain more fluently.

So why does Amazon Prime offer a $99/year membership and not $100/year?

There are two possible reasons: 1) charm pricing is in effect — the $1 difference seems a lot less because of the lower left digit; 2) research shows people assume rounded prices to be inflated — to avoid this, Amazon meets somewhere in the middle by removing the cents.

Although rounded numbers are easier to comprehend, thus giving off the impression that the price is “just right,” humans tend to be suspicious.

So the compromise is to keep the charm price and remove the cents — this gives off the impression of a rounded price. Instead of offering a $99.99/year Prime membership, you make the price seem rounded by offering a $99/year Prime membership.

The next thing you’ll notice is Netflix downgraded its service for the $7.99/month plan. This was a mistake, but a mistake Netflix had to make.

Another way you can look at this is Netflix raised the price of its original service to $9.99. Normally this is a good move for businesses because it raises the reference price and makes Premium services seem more affordable.

However, Netflix made the mistake by still offering the $7.99 plan but downgrading this plan’s service. This reinforces the lower reference price, making the Premium plan seem even more expensive now.

But like I said, this was a mistake that had to be made. Since Netflix chose to grandfather early adopters in when they initially raised prices, they put themselves in a position where they couldn’t just cancel the $7.99 service without upsetting a lot of customers.

What you’re seeing now is a slow shift toward a price plan similar to Amazon Prime. I bet in the next year or two Netflix will only offer: Standard $9.99/mo, Premium $11.99/mo, and a yearly $69/year plan similar to Prime’s $99/year membership.

But first, Netflix needs to get users comfortable paying $9.99/month. To do this, they need to upgrade everyone to $9.99 — which they are doing. Once customers become comfortable, Netflix will ditch the $7.99 plan and probably adopt the three price plan like I suggested. Once this happens, you’ll see a spike in Premium subscribers since the reference price will have been raised.

Current reference price: $7.99, future reference price $9.99.

These tactics should give you some ideas of how to price your subscription service, but there’s one more strategy neither company is using.

What we’ve found at ETR is that there are actually THREE ways subscription services should be offered:

1) Monthly — Netflix and Amazon Prime are doing this.

2) Yearly — Amazon Prime is doing this (and Netflix should consider to get “cash in hand, up front”)

3) Lifetime — this requires you knowing how long people stay on average (which I’m sure Netflix and Amazon do), and then offering an outrageous lifetime deal that gets more than the average lifetime revenue from someone.

For example, let’s say the average stick rate of the annual for Amazon Prime members is 3 years. That means the average revenue is $300.

They should offer a lifetime for $350 that also includes additional bonuses you can’t get in any other package — such as free 1-day delivery (instead of 2), and discounted same day delivery, and one more thing to make it a no brainer. Everyone wins with the lifetime package.

For more pricing strategies, I recommend reading this massive guide by Nick Kolenda.

Nick Papple

Managing Editor

The Daily Brief